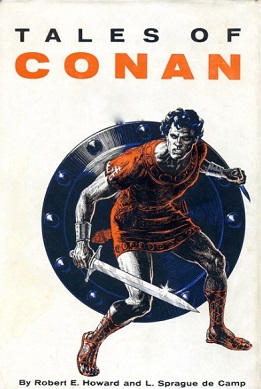

Name: Conan the Cimmerian

Tagline: Conan came from the northern Cimmuria to fight monsters, claim treasure and woo beautiful women. And to become king of Aquilonia, apparently

Claim to Fame: Conan is a barbarian, right? An uncultured, brutal, unsophisticated fighting machine. Well, turns out he’s actually kind of brainy and genteel for a brute.

When most people hear the name Conan the Barbarian, they probably see the muscle-ripped figure of young Arnold Schwarzenegger. Many would probably be surprised to learn that the first we heard from Conan is a story from his old age, in which he has gained the throne of the civilised country of Aquilonia.

The other stories also depict Conan as surprisingly unbrutal and genteel. He fights evil monsters, he saves women in distress, and while he may boast a lot of less-than-honest deeds, we see very few of them on the page.

A while back I read some of the Conan-stories (I still have the omnibus on my shelf). I had expected a written version of the Schwarzenegger character I had seen on the posters, but I remember being surprised at how much I liked the stories, and how nuanced and interesting I found Conan to be.

All this came back to me as I listened to the latest episode of the podcast, Ken and Robin talk about stuff. In this episode, hosts and long-time storytellers and game designers, Kenneth Hite and and Robin D. Laws, talked about Swords & Sorcery, and what characterises the genre. They pointed out that Sword & Sorcery heroes usually has something they oppose. Every monster or foe they encounter is an incarnation of this more general foe.

Conan, they pointed out, fights for order and civilisation against outside forces that want to break down the ordered society. This is obvious in the stories from when he is a king, but is the case in a number of others as well. In one, he serves as a mercenary for a nation beset by evil, supernatural forces.

Now, the word “barbarian” comes from Greek. The word comes from the way non-Greek languages sounded to Greek ears (”bar-bar-bar-bar”), and the ancient Greek used it to refer to uncivilised peoples from other parts of the world (the only real civilisation being the Greek, obviously).

Which, ironically, makes Conan as much of an anti-barbarian as he is a barbarian.

How to use him: Conan is – of course – the prototypical Sword & Sorcery-hero. And I think he has a number of traits to emulate in that genre: he is a gregarious outsider, making it both natural for him to travel alone, and to meet other people. He is a rogue, but he has strong morals, making him relatable. Unlike someone like Elric, who seems a bit too weltschmertz-y for my tastes.

The Barbarian is of course a character archetype in a lot of roleplaying games. But I think it’s interesting to note the significant differences between those characters and Conan. A lot of barbarians are either noble savages, or they are really (viking-inspired) berserkers.

Finally, I think it’s interesting to do what seems to have happened with Conan from the very beginning: to look at him at the end of his journey, and not just in the early days. More stories with heroes at the peak of their careers, and not just at the beginning!

Side note: for another interesting look at a “barbarian” archetype at the end of his career, see the Logan Ninefinger-character from Joe Abercrombie’s First Law trilogy. But where Conan has successfully found a retirement from adventuring through becoming a king, Ninefinger is stuck as a mercenary and roaming fighter. Also, Terry Pratchett has thoroughly subverted the character in the character of Cohen the barbarian, most notably in the book, Interesting Times.

Der er mere Conan-inspireret rollespil på min blog i dag:

Beasts & Barbarians til Savage Worlds