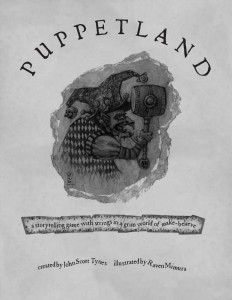

Oh, that wicked Mr. Punch!

Author/Designer: John Scott Tynes

From: The Indie Initiative Bundle

I heard about Puppetland game way, way back, when I first started looking into Indie Games. But alas, it was out of print, and I wasn’t into buying games in pdf.

Flash forward a great many years, and suddenly it popped up in a bundle. So of course I had to get that bundle, so that I could figure out what all the fuss was about.

In Puppetland, you play puppets in a land of puppets. The land was created by the Maker, the human who created all of the puppets, in order to keep all of the puppets safe. But the evil Punch killed the Maker, and took over as ruler of Puppetland.

Now Punch’s former lover, Judy, leads a resistance movement against Punch, while most of the puppets live in fear of the tyrant and his cruel minions. The players will play puppets in this world, trying to overthrow Punch and revive the Maker, so that all will be right again.

The game is a fair bit different than many other early Indie games. This may well be because it originated before the Indie movement really took of; apparently, the first draft of the game was created all the way back in 1995.

The rules of the game are deceptively simple. There are three:

The First Rule: A “tale” or session of the game lasts precisely one hour of real time. After that time, the game will end, and the Puppets will find themselves back in their bed again the next morning. Even if they died during the previous tale. During the hour the game lasts, you can narrate a far longer span of time in the fiction, simply by saying what amount of time elapses.

The Second Rule: When you sit down at the table playing Puppetland, what you say, your puppet says. Including “I reach for the rock to hit the Nutcracker with”. As such, all puppets will be continuously narrating their own actions: “I shall take this rock and hit that mean nutcracker over the head with it”. If someone must break character, they have to stand up from their chair – and ideally go over to the GM to whisper into his ear.

The Third Rule: Everything must be presented as if this was a story being told. This rule is mostly for the GM: The GM should always speak in the past tense, as if narrating a storybook. “The rock hit the nutcracker straight in the back of the head. ‘Crack’ said the nutcrackers head. Then he slowly fell forward and landed on the floor”. Of course, it also goes for the players, who should talk like characters in a storybook. That means that profanity is no good, while the morality of everything that happens is black and white: the good are good, and do nothing evil, while the bad guys are evil through and through.

Characters are created by selecting the kind of puppet (finger, hand, shadow or marionette), giving it a name, writing down what it is and what it can and cannot do, and drawing a picture of the puppet on the character sheet.

The overarching plot of the game is pretty well set – overthrow Punch and revive the Maker – but the individual tales could be anything: overcoming Punch’s minions, getting secret information, saving someone from Punch’s wrath or maybe interfering with Punch’s nefarious doings.

There is no system for combat, except what the GM deems a feasible outcome – bearing in mind that good should be able to carry the day in the end. Death is not usually final – at first. The 16th time a character dies, however, it will be for good.

My impression: Wow. This is a fascinating and disquieting game to read. The immediate impression is very cute and quaint – but when you dive into it, there is a really ugly side to this game. The minions of Punch – his boys are nasty creatures created from the flesh of the maker (!), and you can expect puppets to be tortured and murdered throughout the game for such heinous crimes as being unhappy.

The world of the puppets is described in just enough detail to make it both realistic and absurd. For instance, the puppets have to eat, which means sitting around, pretending to eat. Otherwise, they will grow hungry. The game is full of these quaint little details that give me a really good impression of the feel I’d want the game to have.

The rules… are weird, but I find them strangely charming. Even if they don’t give “proper” resolution mechanics of any kind, they steer the conversation, and give some general guidelines to provide the kind of story it wants. Dice or cards would get in the way, I think, particularly since there’s a limit on the time the game is allowed to take. Including a time limit is not only an unusual thing, I think it would be necessary in a game like this – it’s hard to maintain the kind of focus required to only speak in character for very long, but an hour should be fine. It also helps set the scope of each tale to roughly what could be covered in an evening’s bedtime story reading.

Speaking of that, the game has a conflict between silly children’s story and visceral horror. Where the tone ends up in any given group would depend a lot on the individual GM, and I expect the game to grow darker as the sessions go. I do not think of this as a children’s game, however.

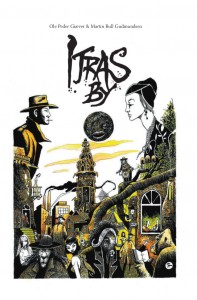

Puppetland is not a game for everyone, but with the right crowd, I think this game could really shine. If you have someone who can relish both the humour and silliness of the puppets and the darker stuff underneath, you could tell some really interesting stories. Incidentally, I think this game has more players in common with Itras By than with Atomic Robo – it has some of the same surreal vibe and communal storytelling that Itras By also has, but not nearly as much action as Atomic Robo.

How would I use this: I would like to try this game out for a few sessions. I don’t think I would want to spend many evenings playing this game – but with hour-long sessions, you could squeeze one into an evening before a board game, or something of that kind.

It’s also a game I think I could play with new players who have a bit of an acting, storytelling or literary bent. Someone who might not want to roll loads of dice, but who can get behind the peculiar acting inherent in this game.