The grand-daddy of indie-games, with commentary by the creator

The grand-daddy of indie-games, with commentary by the creator

Author/Designer: Ron Edwards

From: Indie Treasure Trove

Today I’m looking at the annotated version of Sorceror, taken from the Indie Treasure Trove

bundle. This one has a number of classics, including 3:16: Carnage among the stars and Annalise, just as I was tempted to go with the western game, Dust Devils. But in the end, there was no getting around this game.

See, Sorceror was the game that started it all. The first certified Indie RPG, by the man who created The Forge himself: Ron Edwards. Today, the web is teeming with story games and indie games building on the ideas that grew out of The Forge, but back then, it was a revolution. Now, I haven’t played Sorceror, nor had I read the book till today, so this book was too obvious to pass by.

In Sorceror, you play more or less regular people in an ordinary world. At least on the surface – because in reality, you possess secret knowledge that allows you to summon and bind demons to carry out your bidding. Of course, that is not an uncomplicated thing to do, and so you are fighting to keep up your cover while trying to sate your demon’s needs, just as it helps fulfil yours.

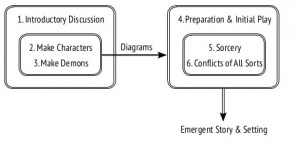

The book is divided into chapters, with each chapter detailing a certain part of the play. Edwards has a little graphic describing this that I thought described it pretty well, so I’ll include it here:

And so, Chapter 1 describes the initial discussion as you’re sitting down to play Sorceror – where and when are we, and how do we envision the magic working? Chapter two is Character generation, while chapter three deals with generating Demons, something that is mostly a task for the GM. Chapter 4 then describes the overall framework for playing the game, while chapter 5 deals specifically with how you deal with demons, and chapter 6 is all sorts of other kinds of conflict you might end up in. I liked the clarity of this visual way of describing both the structure of the book and the flow of the game.

This is the annotated version, so on the left hand side of the book is the original page, while on the right you’ll find present-day Edwards’ commentary on the old text: praise or condemnation for his earlier self, along with clarifications and better ways of doing things.

At the centre of the game are two concepts that have become very famous in indie game parlance: the Kicker and the Bang. The Kicker is created by the player during character generation, and sets out the beginning of the character’s first story arc. It details a conflict, an opportunity or a threat that the character will deal with during play. This should be enough to fuel the character’s story for a few sessions, and by the end of it, the character will have undergone significant changes.

The Bang, on the other hand, is a loaded situation here and now that players have to deal with. Anything from “Ninjas come barging through the door!” to “Your mother is at the door, and the escort you picked up last night is still in the bathroom, freshening up.”

My impression: I can see the appeal of this game. Even today, after so many other games have developed these ideas further, there seems to be a number of really interesting aspects to Sorcerer. Not least the basic premise of being pretty ordinary people, except you can summon Demons to do your bidding and get you everything you desire… for a price. The basic rules seem pretty simple, and I think it provides the tools for interesting play.

Having said that, though, it feels somewhat clunky. The text seems longer than it needs to be, and it doesn’t always explain the concepts of the game very well. At one point, I searched through the whole document for the proper definition of the Bang and how they should work, but it turned out that the book only had a very vague definition and a loose discussion of their role in the game. At other times, the book seems to spend far too much time on concept that are, all things considered, rather straightforward.

Of course, part of the clunkiness comes from the fact that half the book is commentary. This means that in order to understand a concept, you often have to read the original text, then read Edwards’ comments on it to understand how he would do it know, then skim the original text again in order to see how it relates to the commentary. The commentaries are interesting as part of a study of the development of these kinds of games, and the development of Edwards as a game designer, but I found myself wishing he would write an updated version instead, streamlining the rules and integrating 15 years of experience into the main text, making it more accessible.

Speaking of… Something about the commentary bothered me a little as I was reading. It seems a little as if Edwards is ignoring the development that’s happened over the decade and a half since this game out. This particularly stood out to me during the commentary to the start of the first chapter. Edwards writes:

You simply cannot begin preparing and playing in the same old way you’re used to because you “understand role-playing,” and rely on looking things up as you might in many other RPG texts. This goes double for people who’ve been GM for many different games and who consider themselves experienced. (Sorcerer, p. 13)

And a few lines later:

A lot of games shoot for the initial, necessary inspiration by providing a detailed setting. However, Sorcerer begins with building characters. And since the character creation process necessarily wraps them into in a crisis situation, you only need a little bit of setting to make this go. In other words, setting exists at the outset only to supercharge the characters’ immediate hassles, not for the characters to explore. Play itself will make lots more setting (the “complete” setting if you like), which is fine.

Now, I can see how this holds true if you’ve only ever played “trad” games, with complete GM control and great big setting tomes. But take a look at games like Prime Time Adventures, Fiasco or Apocalypse World, and this is exactly what they do. And honestly, the people who are most likely to read this book are the people who are already familiar with the Indie scene, and who will know about the development over the intervening years. As such, it seems odd for Edwards to write like this. I am certain that Edwards is aware of the development in the scene. So has he misjudged the audience for this book so severely (or, I guess, am I misjudging it?), or does he really think that sorcerer is so different from all the games it inspired?

All in all, this is an interesting game, unfortunately presented less clearly than it could have been.

How would I use this: This annotated version of Sorcerer is interesting as a historical document. I wouldn’t mind diving into it a bit more, seeing which lessons Edwards drew, and trying to figure out what that says about the development of the Indie- and Story-game scene.

The game in itself is also interesting, both as in itself and because of the historical significance of it. I would love to try this game, perhaps just for a couple of sessions, to see how it works. It seems like the game might provide a good basis for some interesting and rewarding stories.